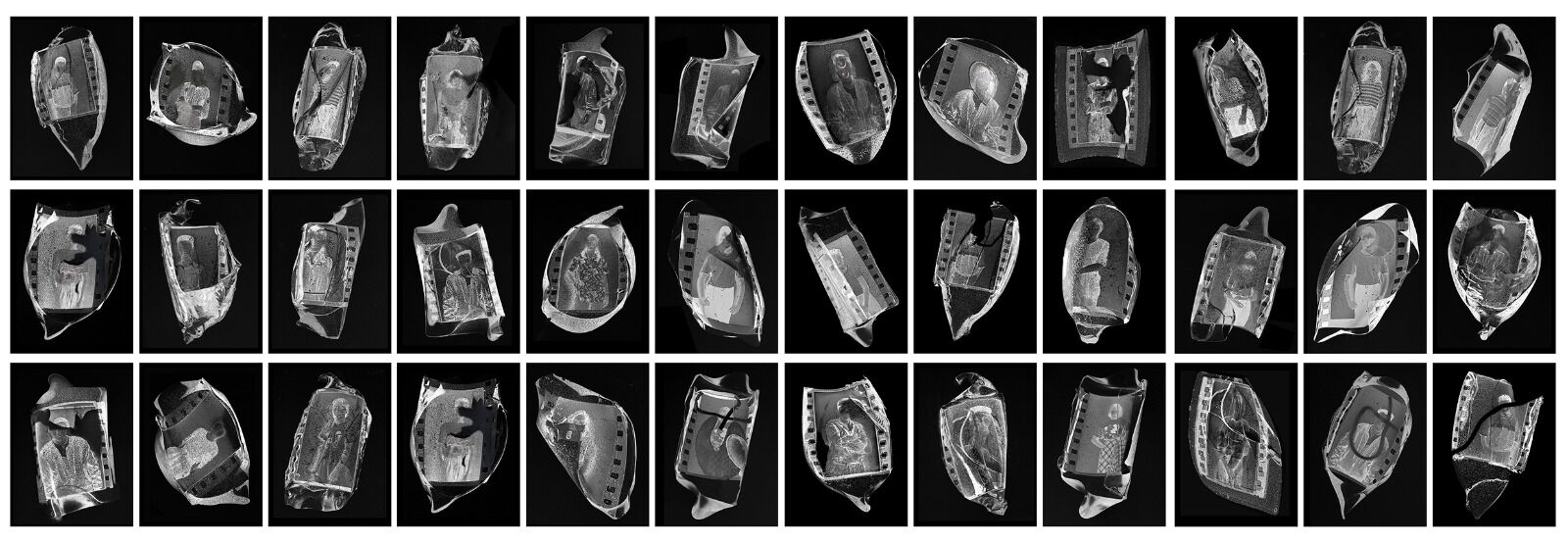

Pavlov's Children, 2024

see book dummy Forgotten Doctrine ( 2025)

https://www.blurb.co.uk/b/12511915-forgotten-doctrine

In 1989, just before the Berlin Wall fell, I was suddenly reassigned from my first teaching post. Years later, I learned from my Stasi file that I had been deemed “unsuitable.” I remembered one vivid moment: during a flag ceremony, students raised handmade signs and chanted for me to stay. Their defiance stayed with me.I returned to my archive and found over 15 rolls of black-and-white film—portraits of my students from those final weeks.

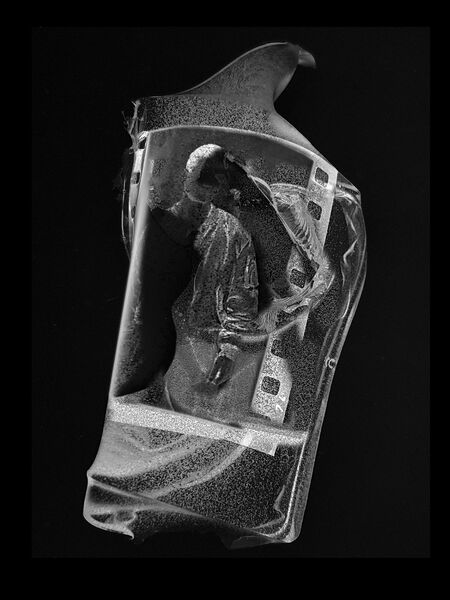

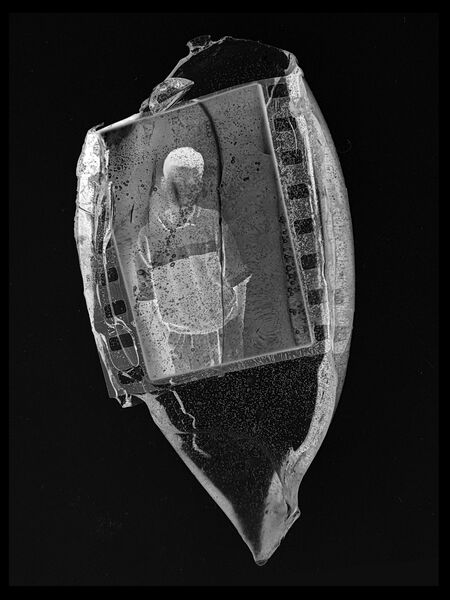

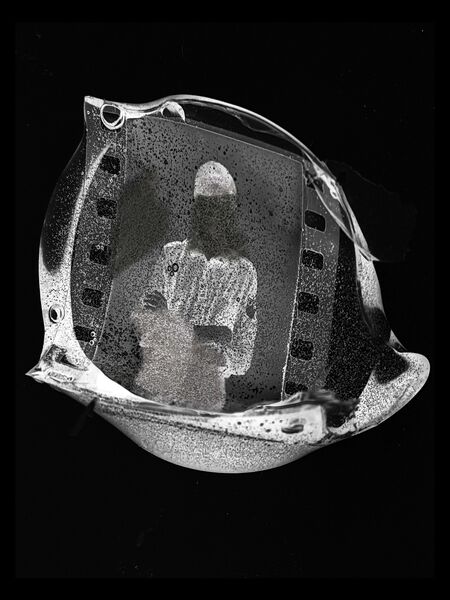

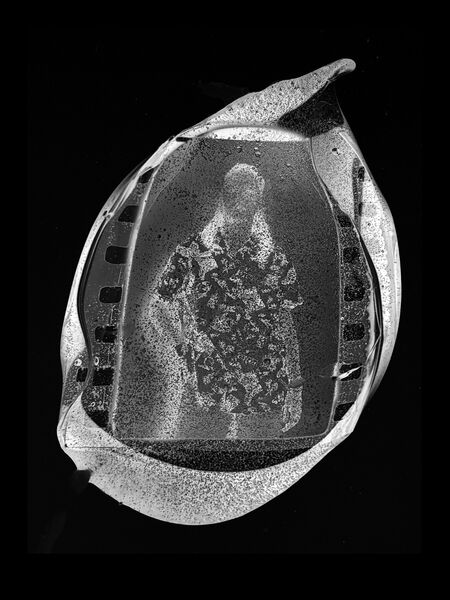

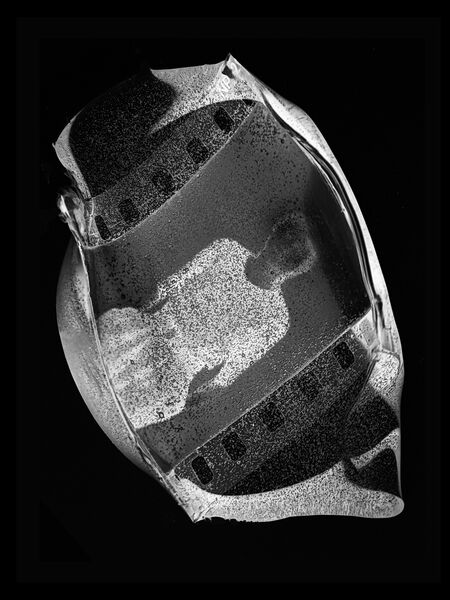

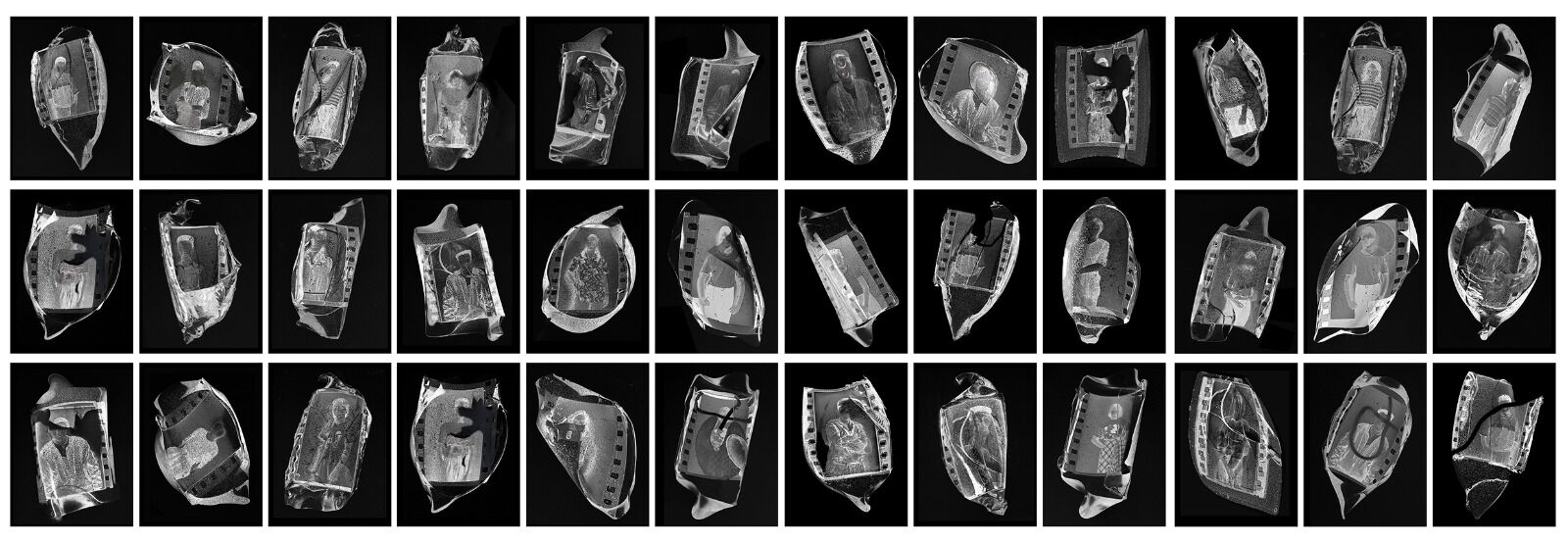

Pavlov’s Children explores how children are conditioned by education and ideology. The title references Ivan Pavlov’s theory of behavioural conditioning, echoing how the GDR shaped young minds. Each negative is encased in resin—distorted and preserved. The resulting one-of-a-kind moulds are photographed and printed on 10 × 8-inch matte paper, arranged in grids.

Through this work, I honour my former students while reflecting on the lasting impact of an educational system designed to condition rather than cultivate.

up to 400 prints ( 10x8-inch) are available

https://www.blurb.co.uk/b/12511915-forgotten-doctrine

In 1989, just before the Berlin Wall fell, I was suddenly reassigned from my first teaching post. Years later, I learned from my Stasi file that I had been deemed “unsuitable.” I remembered one vivid moment: during a flag ceremony, students raised handmade signs and chanted for me to stay. Their defiance stayed with me.I returned to my archive and found over 15 rolls of black-and-white film—portraits of my students from those final weeks.

Pavlov’s Children explores how children are conditioned by education and ideology. The title references Ivan Pavlov’s theory of behavioural conditioning, echoing how the GDR shaped young minds. Each negative is encased in resin—distorted and preserved. The resulting one-of-a-kind moulds are photographed and printed on 10 × 8-inch matte paper, arranged in grids.

Through this work, I honour my former students while reflecting on the lasting impact of an educational system designed to condition rather than cultivate.

up to 400 prints ( 10x8-inch) are available